Islamic Revolution ended Pahlavi rule and dismantled Western hegemony

By Xavier Villar

Iran is commemorating the 45th anniversary of the foundation of the Islamic Republic this week, known as ‘The-Day Dawn’, a watershed moment in contemporary world history that brought about significant changes in the way people look at the world with a different language and political horizon.

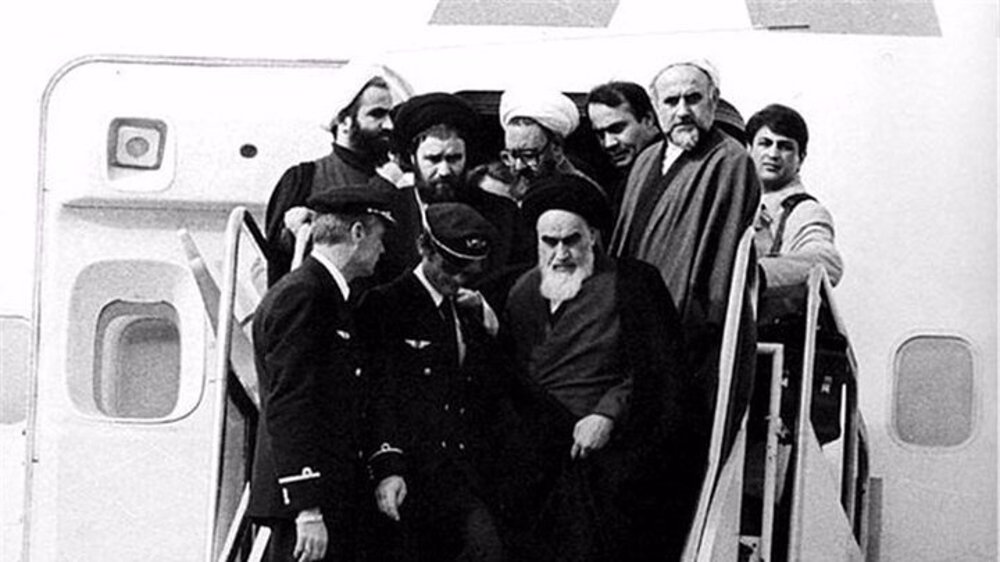

The Islamic Revolution of 1979 spearheaded by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini gave voice and agency to those people who had been portrayed by West-centric historiography as passive and depoliticized.

Precisely, the supposed lack of agency among Muslims led to the consideration of the founding of the Islamic Republic in 1979 as an event outside the norm that was defined by arrogant powers.

It is important to note that the establishment of the Islamic Republic was preceded by a revolutionary movement – the Islamic Revolution – the first-of-its-kind revolution that didn’t follow Western grammar and was different from other classic revolutions like the French, Russian, and Chinese revolutions.

Unlike these revolutions, which in some way stemmed from the same historical-political moment as the ‘Enlightenment’, the Islamic Revolution of Iran diverged from the objectives and direction and slogans associated with the Enlightenment and its goals.

The Islamic Revolution, as well as the subsequent foundation of the Islamic Republic, should be understood from an epistemic perspective, which means that its goal was not merely the overthrow of a corrupt dynasty, but also the overthrow and subsequent replacement of Western political grammar (what some experts refer to as "westernesse").

This grammar, represented in Iran by the Pahlavi dynasty, privileged a set of principles that, in general, hindered the construction of an independent Muslim political identity.

Under “westernesse”, for instance, Islam was perceived as a "religion," defined as a private belief separate from the political sphere. Simultaneously, the Pahlavi regime's view of Islam as a "religion" relied on the necessary existence of secularism discourse.

Secularism should not be understood simply as the absence of religion or its exclusion from the public sphere but as a normative project that sets its own limits.

For the Islamic Republic, secularism is neither natural nor the culmination of a historical process. It is perceived as a disciplinarian discourse, a political modality that validates certain political sensibilities while excluding others by deeming them as a threat.

The Islamic Revolution played a crucial role in dismantling the hegemony of the entire discursive complex known as “westernesse.” This destruction is fundamental to understanding the category of "scandal" previously applied to the foundation of the Islamic Republic.

Through the intervention of Islamic revolutionary politics, the supposedly necessary historical sequence known as "from Plato to NATO" would have been interrupted.

In other words, by mobilizing a different political language, in this case, an Islamic language, the normative idea that the world was the way it was naturally and necessarily was questioned.

The primary consequence of the Islamic Revolution, therefore, was to question the narrative defined by Western ideology and, simultaneously, enable different ways of inhabiting the world in political terms.

So, what was achieved was not just the fall of the West-backed corrupt and authoritarian Pahlavi dynasty but the provincialization of the West: westernesse ceased to be the only possible language.

The revolutionary moment marked the return of the political. It is important to differentiate the term "the political" from the more common and mundane term, which is "politics."

The political represents the moment of openness, destabilization, and disarticulation of the status quo, and thus, the emergence of new possibilities for inhabiting the world.

On the other hand, "politics" refers to the moment of sedimentation and normalization. Both moments are necessary, and at the same time, their coexistence is always unstable.

Following this framework means the founding of the Islamic Revolution marked the culmination of the revolutionary phase that took years and thousands of lives.

Having said that, it is crucial to analyze the foundation of the Islamic Republic in 1979 by Imam Khomeini not as a theological act but as a political one.

However, this act was derived, as mentioned earlier, from a specific language with Islam at its core.

This approach is reflected in a set of Islamic principles that form the basis upon which the entire political framework of the current Islamic Republic stands. These principles tell a story of a struggle against injustice and oppression, represented both by the Pahlavis and the dominance of Western ideology.

The struggle against injustice encompasses two dimensions reflected in the foundation of the Islamic Republic. On the one hand, there was a will to defend Muslims against the injustices of the world. To achieve this, it was necessary to build an Islamic power capable of protecting the Ummah.

This Islamic power would be the guarantee of an independent Islamic presence in the contemporary world, and its absence would mean that Muslims would not be politically represented on a global level.

On the other hand, this struggle against injustice must be understood from an existential-ontological perspective: it involves a constant march towards an ethical horizon that serves as a guide, never entirely achievable but always present.

This existential-ontological perspective is reflected in the Quranic story of the Pharaoh. This figure becomes an archetype of everything that injustice signifies. The Pharaoh is a symbol of absolute authority understood in authoritarian and despotic terms.

As such, it represents the absence of all compassion and the implementation of political-economic systems based on injustice and tyranny. At the same time, the Pharaoh commits the crime of transgression by attempting to replace the divine figure.

The foundation of the Islamic Republic is understood as part of the existential struggle against injustice and oppression. In the narrative of the Islamic Republic, it is maintained that any political moment dominated by injustice and the brutalization of oppression is destined for destruction.

The foundation of the Islamic Republic, as well as all political acts derived from it, is framed within the struggle against injustice.

Therefore, understanding the Islamic Republic means comprehending the rejection of Western language, the need to articulate independent political visions, and opposition to all political entities that transgress and attempt to build hierarchies based on oppression.

Xavier Villar is a Ph.D. in Islamic Studies and researcher based in Spain.

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Press TV)

UK ordered in 'milestone' court ruling to pay $570 million for colonial-era massacre

VIDEO | Defying the rubble, Gaza opens its first face-to-face school since start of war

‘Ready for next round’: Million-man rally in Yemen backs Gaza, resistance

FM Araghchi departs Muscat for Doha following nuclear talks with US

Israeli keeps killing more Palestinian civilians in Gaza amid relentless ceasefire violations

Aliyev: Azerbaijani territory will not be used for threats against Iran

Turkey arrests two on charges of spying for Israeli regime

Iran FM declares ‘good start’ as US–Iran talks conclude in Muscat

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website