Remembering Saadi Shirazi, Persian poet whose message of universality endures

By Humaira Ahad

On the evening of April 18, 2024, Iran’s late Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdollahian was at the United Nations, participating in a high-level meeting on Gaza’s humanitarian crisis amid the US-backed Israel’s genocidal war on the besieged Strip.

Amirabdollahian’s powerful speech captured global attention when he concluded his speech with an iconic poem by the great Iranian poet Saadi Shiraz—the poem that is woven into the carpet gifted by Iran to the world body, hanging on the wall of the UN building.

“That very carpet is a symbol of strategic patience, knowledge, art, and the strength of Iran and all Iranians around the world,” he stated.

بنی آدم اعضای یک پیکرند

که در آفرينش ز یک گوهرند

چو عضوى به درد آورد روزگار

دگر عضو ها را نماند قرار

تو کز محنت دیگران بی غمی

نشاید که نامت نهند آدمی

“Of One Essence is the Human Race,

Thus has Creation put the Base.

One Limb impacted is sufficient.

For all Others to feel the Mace.

The Unconcerned with Others' Plight,

Are but Brutes with Human Face.”

The poem titled “Bani Adam,” or “The Sons of Adam,” emphasizes the interconnectedness of all human beings and advocates for empathy and compassion in society.

The oft-cited poem is widely considered one of the masterpieces of the Persian poet’s seminal poetic collection, “Golistan.”

Saadi Abu-Muhammad Mosarref–al-Din Muslih al-Din bin Abdullah bin Mosarref Shirazi was one of the greatest Iranian poets of the medieval period.

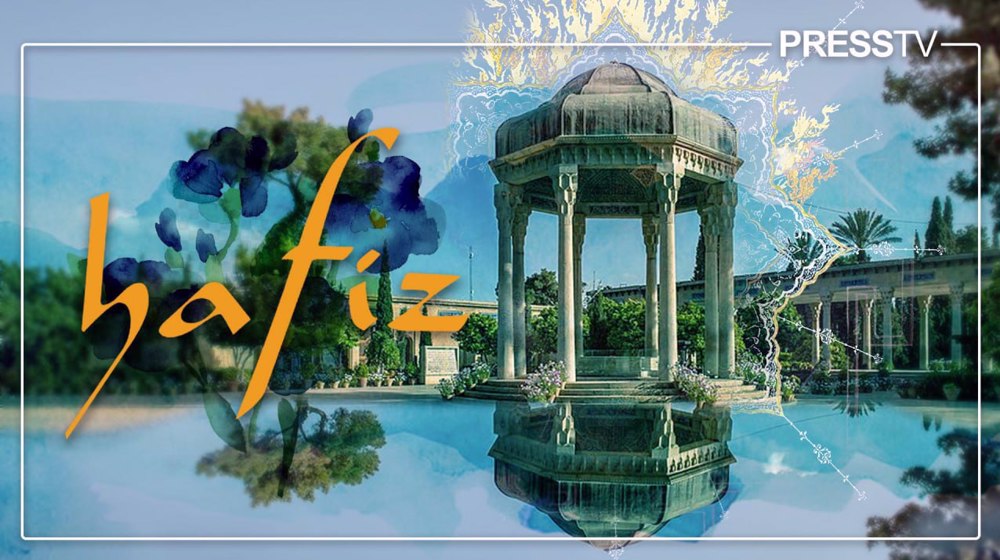

He was born in 1210 and died in 1291 or 1292 in the south-western Iranian city of Shiraz. On April 21 every year, Iranians mark the National Commemoration Day of the renowned Persian poet.

Due to the Mongolian invasion of Iran, Saadi was displaced, which led to the beginning of the Persian poet’s 30-year journey around the world.

After leaving Shiraz, he enrolled at the Nizamiyya University in Baghdad, where he studied Islamic sciences, law, governance, history, Persian literature, and Islamic theology.

The famous poem by the great Persian poet Saadi Shirazi seen on the uniform of an Iranian rescuer dispatched to quake-hit Turkey:

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) February 17, 2023

"Human beings are members of a whole

In creation of one essence and soul

If one member is afflicted with pain

Other members uneasy will remain" pic.twitter.com/7SpT7YdBME

After completing his studies, he travelled across West Asia, India, Central Asia, and possibly North Africa. He found diverse cultures, social structures, and moral philosophies in these areas of the world that enriched his perspective on humanity and ethics.

In his works, Saadi tells many interesting anecdotes of his travels. He also mentions the grandeur of Islamic civilization through its culture, art, grand bazaars, music, etc.

The tumultuous political scenario forced him to live in desolate areas. He sat in remote tea houses exchanging views with merchants, farmers, preachers, wayfarers, Sufis, and even thieves.

Saadi returned to Shiraz before 1257 CE. In the same year, he finished the composition of his poetic work, Bostan.

Saadi Shirazi’s works

Bostan (The Orchard), completed in 1257, and Golestan (The Rose Garden), completed in 1258, are considered masterpieces in Persian literature.

Both works represent Saadi’s eloquent style, wit, and profound insights, earning the Iranian thinker the title of “Master of Speech” in Persian literature.

His competence to convey deep moral lessons through simple, accessible language made his writings timeless and beloved by readers across countries.

Bostan is entirely in verse, consisting of stories aptly illustrating the moral virtues of justice, liberality, modesty, and contentment. The poems also evoke a desire in the readers to reflect on the behaviour of Sufis and their ecstatic practices.

Golestan, on the other hand, is mostly prose. Saadi's prose style, described as "simple but impossible to imitate," flows naturally and effortlessly.

Golestan contains allegorical stories that act as a guide for morality and ethics. The stories provide insights into human nature, morality, and the responsibilities of leadership. Saadi admires the kings who befriend the poor and praises the eminence of the religious ascetic.

Saadi’s works demonstrate his profound awareness of the ephemerality of human existence.

In his books, the famous poet-philosopher laments the fate of those who are after material possessions and depend on the changing moods of the rulers. He compares their state to the freedom of the mystics, regarding the latter as the genuine purpose of existence.

Saadi Day: Ayatollah Khamenei exalts great Persian poethttps://t.co/t8rpQ2evio

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) April 20, 2024

In his Bostan, Saadi uses the mundane world as a springboard to propel man beyond the earthly realms. The imagery in Bostan is subtle, taking the readers on divine flights.

In Golestan, on the other hand, Saadi tries to touch the heart of his fellow wayfarers.

In addition to Bostan and Golestan, Saadi also wrote four books of love poems (ghazals), in Persian and Arabic. The ghazals are collected in four books: Tayyibat, Bada’i, Khawatim, and Ghazaliyat-e Qadim.

Saadi Shirazi inspires the West

The famous American essayist, Ralph Waldo Emerson, called Saadi “the poet of friendship, love, self-devotion, and serenity.”

“He inspires in the reader a good hope.”

Andre du Ryer, a French orientalist, was the first European to present Saadi to the Western world. In 1634, Ryer partially translated the Golestan in French.

Adam Olearius, a German author and diplomat, followed soon with a complete translation of the Bostan and the Golestan in German in 1654.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the most renowned poet of German literature, who was deeply interested in the East and Islam, was also inspired by the Persian thinker.

“The 13th-century poet Saadi (d. 691/1292) was another source of inspiration for Goethe.

The extent to which Saadi had made an impression on Goethe was pointed out as early as 1834 by Chr. Wurm, who had collected and collated parallel passages from Goethe’s Divan and his Oriental sources in his Commentar zu Göthe’s west-östlichem Divan,” writes Judith Pfeiffer in Goethe and Sa‘dī: Christian Wurm’s interpretation of “Selige Sehnsucht” revisited.

Pfeiffer is an emeritus fellow of Arabic/Islamic History at the University of Oxford.

Von Hammer Purgstall, the Austrian orientalist, had singled out Saadi as an unsurpassed “moralischer Didaktiker” (moral educator) in his Geschichte der schönen Redekünste Persiens, and Goethe agreed with this.

Saadi Shirazi, the 13th century Iranian poet, one of the major figures in Persian poetry#Iran #MustseeIran #art pic.twitter.com/HhNM3vnbBm

— Press TV 🔻 (@PressTV) September 9, 2015

In his Lectures on Aesthetics, the famous German philosopher, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, regarded Saadi as a master of didactics.

“There followed also a turn toward the didactic, where, with a rich experience of life, the far-traveled Saadi was master before it submerged itself in the depths of the pantheistic mysticism...,” Hegel wrote.

Emerson, who contributed to some of Saadi’s translated editions, compared the Iranian poet’s writing to the Bible in terms of its wisdom and the beauty of its narrative.

‘Bani Adam’: The universal verses

The poem that adorns the wall of the United Nations emphasizes the interconnectedness of all human beings and advocates for empathy and compassion in society.

Experts believe that Saadi might have drawn the inspiration for the poem from one of the traditions (Hadith) of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him):

“The believers in their mutual love, compassion and sympathy are like a single body. When any limb aches, the whole body reacts with sleeplessness and fever.”

Quoted by politicians, musicians, actors, and people from different walks of life, the poem is widely considered one of the masterpieces of Saadi’s Golestan.

The philosophical message of “Bani Adam” revolves around the concept of human interconnectedness and the moral responsibility to alleviate suffering.

Initially composed in the 13th century, the poem has continued to captivate readers across cultures and generations, leaving an indelible mark on literature.

This depiction of humanity being a single organism, where one part feels the pain of another, creates a poignant image of interconnectedness and empathy. The imagery of the human body and its diverse parts also accentuates the idea of unity in diversity.

US approves $3 billion deal for sale of F-15 equipment to Saudi Arabia

At least 20 killed in heavy Israeli bombing of displacement tents in Gaza

VIDEO | Venezuelans mark one month since US kidnapping of President Nicolas Maduro and his wife

Iran intel minister: West will face consequences over IRGC designation

Pakistan deploys helicopters, drones to retake town from insurgents

Israel-Palestine head of HRW resigns over blocked report on Palestinians right of return

VIDEO | Iranian athletes seal historic year with global titles amid external pressure

An uprising against oppression of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website