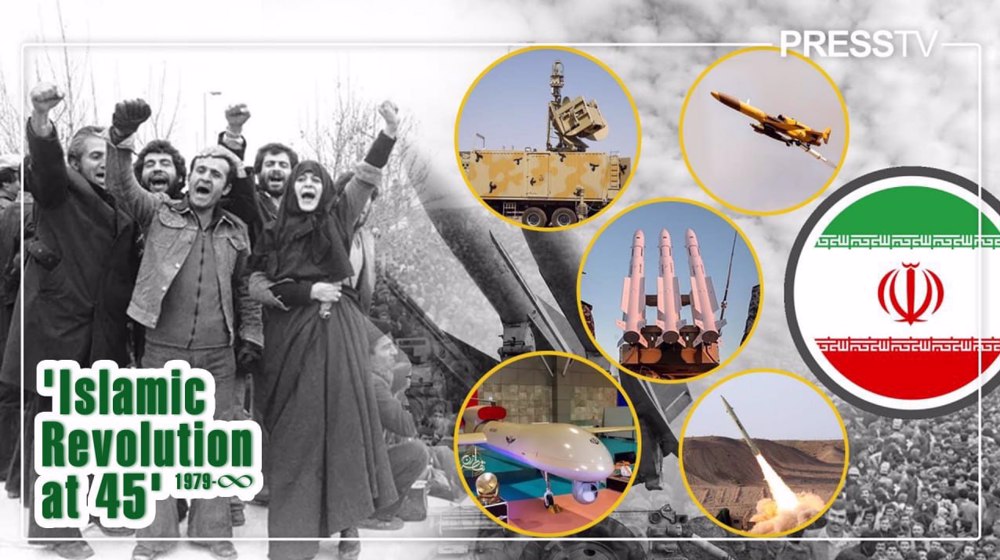

Islamic Revolution at 45: How Iran became global leader in missiles and drones

By Ivan Kesic

In February last year, the British daily Guardian published a report, citing analysts at the US Defense Intelligence Agency saying that Iran is emerging as a “global leader” in the production of drones.

The admission came more than a decade after Washington-headquartered magazine The Atlantic ridiculed a report published in Iranian media about a drone that could take off and land vertically.

"What they didn't tell us is that they used Photoshop to make it stop taking off from the roof of Japan's Chiba University, which built the aircraft and never had anything to do with Iran's alleged version of it,” read the report, questioning Iran’s capability to manufacture drones.

Today, Western countries acknowledge that Iran is a drone as well as a missile power in the world.

The country has taken giant strides in the post-Islamic Revolution era, transforming itself from an importer of military technology to a global leader in cutting-edge missiles and drones.

What preceded the development?

Before the Islamic Revolution, during the reign of the pro-American dictator Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Iran enjoyed the reputation of a military "power" only on paper.

It imported thousands of tanks, hundreds of airplanes and helicopters from Western countries, including the US, as there was no indigenous development or production of advanced military equipment.

Rich reserves of fossil fuels were extracted by foreign companies with foreign technology, and exported for foreign currency, which was spent on foreign technology and the Pahlavi ruler's extravagance.

Iraqi Baathist aggression against Iran during the 1980s, aided by the US and Western powers, exposed the true state of Iran's military strength and the fatality of import dependence.

Following years of fierce warfare, military hardware became unusable due to the scarcity of spare parts that Iran could not import due to the imposed embargo and sanctions.

The aggressor's invasion was eventually repelled thanks to tough resistance of Iranian forces and technological improvisations, so Iran entered the 1990s militarily weakened and with frequent threats from the United States, which was then the world's undisputed superpower.

Missile and drone development

The process of Iran's development of ballistic missiles kicked off in the mid-1980s as an urgent need, due to relentless Iraqi Baathist attacks on Iranian cities using weapons supplied by the West.

Ballistic missiles were a suitable retaliatory response since the aerial bombardment risked the loss of valuable aircraft for which it already was grappling with the issue of spare parts.

At the same time and for similar reasons, Iran began the development of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) for reconnaissance, which made it one of the pioneers in modern military drones.

Under the leadership of Hassan Tehrani Moqaddam, a celebrated engineer and manager from the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC), Iran began ballistic development from scratch.

First, it imported older models of ballistic missiles from very few friendly countries, then copied them by reverse engineering, and continued to design and improve its indigenous missile models.

During the last two years of the imposed war, Iran had Oghab and Nazeat, short-range tactical ballistic missiles or rocket artillery systems, with 45 km and 100 km range, respectively.

After the war ended, their development paved the way for the new Shahab and Zelzal missile families with a range of hundreds of kilometers.

By the late 1990s, Iran produced Shahab-3, its first medium-range ballistic missile (2,000 km), which has virtually all hostile foreign military bases in the region within its range.

Although the system was an adequate deterrent, it was large and unwieldy to transport, it took a long time to fill with liquid fuel, and its circular error probability (CEP) was high and suitable for targeting large enemy bases.

The system was also relatively expensive and produced in limited quantities of a few hundred pieces, disproportionately in a potential conflict against an enemy with larger aviation.

Subsequent medium-range ballistic missiles such as the Ghadr-110, Fajr-3, Ashura and Sajjil, introduced in the second half of the 2000s, brought significant improvements in solid propellant propulsion, shorter preparation and accuracy, but were still large and expensive systems.

Shortcomings with massive medium-range ballistic missiles were compensated during the 2010s, when new variants based on the Fateh-110, a short-range solid-fuel missile with an initial range of only 200 to 300 km, entered operational service.

With the development of rocket engines and related technology, these new variants based on Fateh-110 increased the range over time – Fateh-313 to 500 km, Zolfaghar to 700 km, Dezful to 1,000 km, and finally Kheibar Shekan to 1,450 km.

Their range, therefore, equaled that of older generations of missiles, and although they are equipped with somewhat smaller warheads, with 500 to 700 kg of high explosives, they are still lethal.

The newer and smaller missiles are also more mobile for transport, faster and simpler to launch, more maneuverable and harder to shoot down for enemy air defense systems, with high precision.

In addition, they are easier to produce on a mass scale and can be assembled in huge numbers, as Iran has already confirmed by showing footage of vast missile arsenal from underground bases scattered across the country.

In parallel with the development of ballistic missiles, Iran has invested massively in developing a powerful fleet of combat drones (Shahed, Fotros, Mohajer, Kaman) and loitering munitions (Shahed, Arash, Raad, Meraj), the range of which also covers the entire region.

Rules redefined

With this arsenal, Iran compensated for its aviation shortcomings because it has the capability to target hostile positions with the same range, lethality and intensity, and better cost-efficiency.

It also placed it in a unique position in the world, since all other countries base their long-range firepower on aviation, mostly imported or less often domestically produced.

In both cases, it can be costly and have ineffective results, as evidenced by over a trillion dollars invested in the development of the most expensive jet fighter, as well as the failure of air aggression against Yemen.

Few other countries also have a ballistic arsenal, but these are a legacy of 20th-century global military doctrine and serve to carry weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and deter the enemy, not for precision strikes.

Some countries also produce their own drones and stray munitions, but no such arsenal has proven itself in wartime and does not have the worldwide reputation of Iran's products.

The exceptional efficiency is today recognized even by experts and media of hostile countries, the same ones who years ago tried to downplay or ridicule Iran's military technological innovations.

US imposes ‘terrorist-grade sanctions’ on UN expert, ICC judges amid Gaza accountability drive

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Senior Russian general shot and wounded in Moscow: Officials

UK ordered in 'milestone' court ruling to pay $570 million for colonial-era massacre

VIDEO | Defying the rubble, Gaza opens its first face-to-face school since start of war

‘Ready for next round’: Million-man rally in Yemen backs Gaza, resistance

FM Araghchi departs Muscat for Doha following nuclear talks with US

Israeli keeps killing more Palestinian civilians in Gaza amid relentless ceasefire violations

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website