#ItShallNeverBurn: Raeisi’s UN speech and phenomenon of Islamophobia

By Xavier Villar

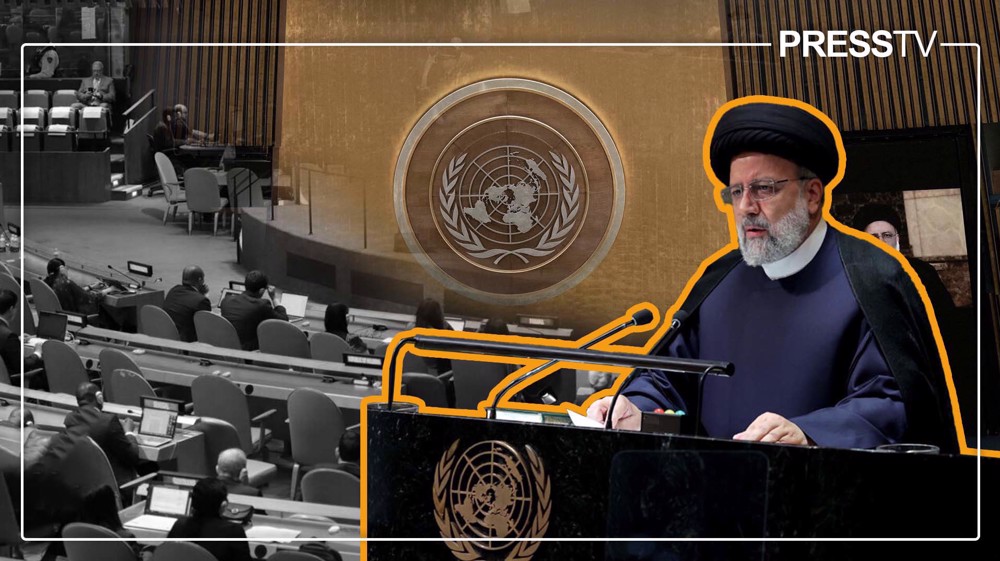

President Ebrahim Raeisi’s thunderous speech to the UN General Assembly in which he denounced the desecration of the Holy Quran and called out the hypocrisy of Western governments, inspired the Press TV website’s campaign that has been trending globally.

This global campaign with hashtag #ItShallNeverBurn succinctly conveys the message that the sacred Muslim book cannot be desecrated as it is eternal and immortal.

President Raeisi was reacting to a series of incidents of Quran burnings in Sweden and Denmark under state protection and patronage, which sparked anger and outrage across the Muslim world.

It is worth noting that these are not isolated incidents of Quran burnings in the West. In 2010, American pastor Terry Jones organized the "International Burn a Quran Day," an event that was ultimately canceled due to heavy backlash.

The burning of copies of the Quran cannot be understood without considering the global nature of the phenomenon of Islamophobia, which is a form of racism directed at Muslims.

Racism does not merely revolve around the belief that humans are divided into 'races,' nor is it limited to the ideology that asserts one race's superiority over others.

Instead, it represents a form of governmentality. Governmentality based on racism implies that the crucial aspect is how populations are organized, disciplined, and regulated.

The reaction of Muslims to the burning of copies of the Quran allows us to analyze the two antagonistic positions that can be found within the Ummah.

On one hand, we have those Muslims who adopt a stance that we could characterize as a "condemnation policy.” On the other hand, there are Muslim populations that opt for a "rejection policy."

The first of these political stances represents an embodiment of respectability politics that is activated after every violent and morally questionable event involving Muslims.

This position aims to pacify the non-Muslim population, which often finds itself in a constant state of anxiety due to the public and political presence of the Muslim community in their societies.

The "condemnation policy" is ready to sanction and censor any response from Muslims that deviates from the image of the "good Muslim."

In the specific context of Quran burning, this "condemnation policy" implies that the "good Muslim" must publicly point out those Muslims who, due to their lack of objectivity and rationality, do not accept the political and social conventions of modern and liberal societies.

This dichotomy between the "good Muslim" and the "bad Muslim" perpetuates the illusion of multiculturalism and tolerance in the West.

However, in reality, this dichotomy consistently generates a discourse that promotes the idea of a national community without divisions. In other words, the "good Muslim," in their role as a political intermediary of the West, upholds the notion that racism is merely a matter of lack of knowledge or that Islamophobia can be resolved through greater education.

At the same time, this "good Muslim" disciplines the rest of the Muslim community by constantly emphasizing the need to respect tolerance and coexistence, without considering the racial underpinnings upon which that supposed tolerance is based.

This figure is the first to condemn Muslims who express their discontent in a political and public manner.

The role of the "good Muslim" obstructs the understanding that the possibility of accessing the nation-state, always in a temporary and contingent manner, has been constructed by denying the political agency of Muslims. The function of the good Muslim is to identify any deviation that departs from docility and categorize it as radicalization.

As a result of this, Islam, as a political identity, gradually weakens as it is required to demonstrate its civilizational aspirations under scrutiny focused on human rights, women's rights, and secularism, all of which are used to seek signs of modernity.

It is precisely the so-called "rejection policy" that halts the erosion of Islam as a political identity. This "rejection" consequently extends to liberal conventions and the idea of the nation-state as the limit of the political.

Returning to the #ItShallNeverBurn campaign, two specific objectives can be identified here: On one hand, is the concrete denunciation of the burning of the Quran, and on the other, the articulation of a political stance that aligns with the 'rejection policy.'

It is an attempt to continue re-politicizing Islam and, at the same time, maintain the rejection of the Western hegemony.

The two stances found within the Ummah, that of the good Muslim and the bad Muslim, also maintain two readings of the Quran: on one hand, the reading that regards the Quran as a sacred text limited to serving as a moral guide, and on the other hand, a sacred and political text that continues to inspire Muslims in their struggle against oppression in its various forms and manifestations.

It is this second reading that corresponds to the campaign launched by the PressTV website, which prevents Islam from becoming a museum piece without the capacity to influence the world politically.

Xavier Villar is a Ph.D. in Islamic Studies and researcher who divides his time between Spain and Iran.

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Press TV

IRGC launches new wave of retaliatory missile strikes on US bases across region

VIDEO | Iranian flotilla returns after BRICS naval drill in S Africa

Iran FM says school massacre in latest Israeli aggression ‘will not go unanswered’

Iran’s retaliatory attack completely destroys sophisticated US radar system in Qatar

US-Israeli aggression violates UN Charter; Iran will defend homeland: Foreign Ministry

US-Israeli 'regime change' project in Iran 'impossible mission': FM Araghchi

IRGC Navy pounds US MST ship with a volley of missiles after Israeli-US aggression

Iran’s retaliatory attacks will continue uninterruptedly: Senior commander

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website