How global cultural memory lifts veil on less-known aspects of Gen. Soleimani’s personality

By Sheida Islami

In October 2019, the top Iranian anti-terror commander responded to a letter from Abu Khaled (Mohammad Deif), the commander-in-chief of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, and clearly stated his position on Palestine and his support for resistance in the region.

“Anyone who hears your call and does not come to your aid is not a Muslim… Assure everyone that Iran will not abandon Palestine. Defending Palestine is a manifestation of defending Islam,” read the letter.

“Defending Palestine is an honor for us, and we will not relinquish this duty in exchange for anything. With God’s help, the dawn of victory is near, and the death knell of the aggressor Zionists has begun to ring. I hope that God will help us to stand by your side and grant us the wish of martyrdom on the path to Jerusalem al-Quds.”

No one knew that a commander with such lofty ideals and objectives beyond geographical borders would, only four months later, attain his long-cherished aspiration near the Baghdad International Airport.

Because of a lifetime spent confronting various “isms” that sought to tear West Asia apart from within and without, he would be etched forever into the memory of humanity, and the title “Martyr of al-Quds” would be added to his medals of honor.

Yet the life of General Qassem Soleimani did not end at the Baghdad airport.

The man of all seasons of resistance continued after his martyrdom, and although many aspects of his life remain untold, he has become one of the most compelling subjects of the six years that have passed since his cowardly assassination ordered by Donald Trump.

We examine how his heroism has been reflected in selected works of written and visual literature.

Qassem Soleimani and the literature of resistance

Before becoming synonymous with the name Qassem Soleimani, the literature of resistance spoke louder than lived experience. Rather than being nourished by individual life stories and concrete decisions, it leaned on overarching ideals. Its hero was often collective, limited in scope, or rendered in abstract terms.

Noted resistance figures such as Imad Mughniyeh, Sayyed Abbas Mousavi, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, and others had featured before him, but the emergence of Qassem Soleimani, not merely as a military commander, but as an ethical actor in the field whose sphere of action and influence extended far beyond that of his predecessors, gradually reshaped this narrative.

Although Persian-language literature of the Sacred Defense (the eight-year imposed war of Iraq against Iran) had already produced thousands of documented works, novels, and oral histories about martyred commanders, and although the struggles of Iran’s revolutionary leaders and self-sacrificing figures constituted part of the country’s written heritage, literature before General Soleimani had rarely had access to an almost mythical figure operating across vast, multidimensional domains of war.

Moreover, the emergence of a mysterious, shadowy figure like General Soleimani in the public imagination compelled the world itself to change its language – to grow calmer, write more precisely, and instead of issuing destructive or justificatory statements about assassinating such a commander, to observe the many dimensions of his life, his ethical legacy, and the more human aspects of a military hero.

From his childhood in Qanat-e Malek, a small town in Kerman province, to commanding the Quds Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC), General Soleimani’s life was centered on a narrative that did not conform to classical rules of hero-making. He was not a product of media construction, nor did he have any interest in narrating about himself.

This conscious absence from the image only intensified the thirst to narrate his life and times. Writers, journalists, and documentary filmmakers encountered a man who fought but did not write; who made decisions but did not explain them.

Precisely for this reason, literature was forced to take its task more seriously. What gradually emerged was a restrained language, grounded in detail, even filled with meaningful silences that only heightened the commander’s allure.

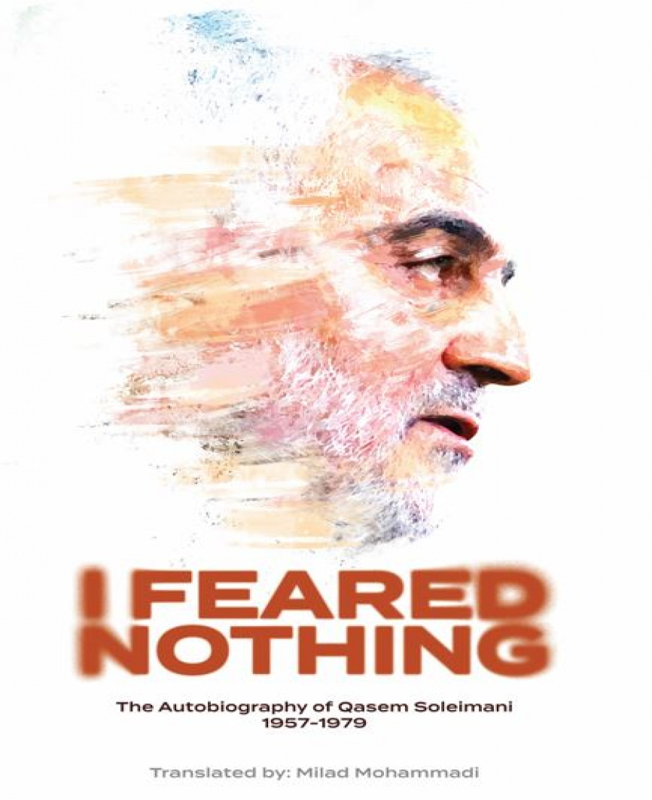

The most foundational Persian text in this transformation is the book Az Cheezi Nami Tarsidam ("I Feared Nothing"), General Soleimani’s autobiographical memoir. Its importance lies not in its literary construction but in its status as a primary source.

Here we encounter not interpretation, but first-hand testimony. The narratives are brief, unadorned, and often devoid of moral conclusions. General Soleimani does not explain why his actions were right; he simply states what he did. This absence of judgment lends the text a power that many other laudatory works lack.

Although the book narrates his life only up to the middle of his revolutionary activities in 1979 (the year of the Islamic Revolution), from a discursive standpoint, I Feared Nothing offers a vivid picture of the roots of General Soleimani’s personality and existential foundations.

With simple language and an intimate tone, it neither promises the future nor embellishes the past, but portrays a formative period in the life of the greatest contemporary military commander of West Asia – the period that made him who he was.

The book’s media function is decisive: almost all serious subsequent works consciously or unconsciously refer back to this text.

The book Haj Qassem ki Man Mishinasam ("The Haj Qassem I Know"), written by Saeed Allamian, recounts the 44-year friendship between Hojjat al-Islam Ali Shirazi and the great martyr. This work adds another layer to the puzzle of his personality and focuses on the post-revolution years.

It deliberately moves to the margins – to non-heroic moments and everyday behavior. The narrative is centered not on the battlefield, but on the field of human relationships.

Its function within resistance literature is to shatter the one-dimensional image of a commander, revealing aspects such as his reading habits, personal and family conduct, and his behavior toward his wife and children.

Many regard Sarbaz Qassem Soleimani "The Soldier of Qassem Soleimani" as one of the most complete biographies written about him to date. Although many untold aspects of his life remain undocumented and numerous peaks and valleys of his 40-year presence at the heart of major events and operations in Iran and West Asia remain concealed, the author, Mostafa Rahimi, has sought, within the limits of available information, to document his military and political achievements, examine his strategic genius in the Syrian and Iraqi battlefields, and trace the hardships he endured to restore stability to the region.

Alongside these works are books such as Haj Qassem Rafiq Khoshbakht Maa ("Haj Qassem, Our Fortunate Friend") by Mohammad and Asadollah Mohammadi-Nia, which reflect General Soleimani’s image in the words of Leader of the Islamic Revolution Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei, Martyr Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, and General Soleimani’s own will.

Others are Zulfiqar, compiled by Ali Akbari Mazdabadi, which recreates oral memories from the Sacred Defense era to General Soleimani’s struggles in the Syrian and Iraqi resistance fronts; and Qassem, narrated by Morteza Sarhangi, which documents six decades of Soleimani’s life, from birth and childhood in the rural and tribal areas of southern Kerman to his martyrdom at Baghdad Airport, while also serving as a comprehensive source for understanding Iran’s regional policies through the lens of resistance diplomacy.

Among the hundreds of books written about this prominent figure of resistance, children’s and young adult works published by the “School of Haj Qassem” are not marginal, contrary to common belief.

These texts avoid excessive simplification and sloganeering, focusing instead on concepts such as responsibility, courage without violence, and personal ethics in the face of social duties.

Functionally, these works aim to demonstrate how General Soleimani has become a “symbolic educational capital” – a personality that can be translated into the language of future generations.

Qassem Soleimani and the cinema of resistance

In Persian cinema and documentary films, a shift in perspective on the concept of the qaharmaan melli (“national hero”) is clearly evident.

Payeez Panjaah Saalgi ("Autumn of Fifty"), directed by Mohsen Eslamizadeh, examines General Soleimani’s presence in southeastern Iran after the end of the imposed war and how lawlessness was dismantled in the region. At the time, southern Kerman, Sistan-Baluchestan, and surrounding areas were highly insecure, and General Soleimani was tasked with securing them through a special headquarters.

The distinctive documentary Chand Qadam Aan Taraf Tar ("A Few Steps Away), directed by Mohammad Salehi, focuses on Soleimani’s protection team. Its title refers to a condition Soleimani himself set: that his guards always remain “a few steps away” so there would be no barrier between him and the people.

Reddi Az Yek Mard ("Trace of a Man"), directed by Sasan Fallahfar, recounts memories of Soleimani through the voices of residents of Qanat-e Malek, his birthplace, where nearly everyone holds personal memories or keepsakes of him.

72 Saat ("72 Hours"), directed by Mostafa Shoghi, examines the final 72 hours leading up to the martyrdom of General Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis amid turbulent conditions in West Asia, particularly Iraq.

In those final days, he traveled to Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq to personally assess the situation and consult resistance commanders. Produced over two years, the documentary combines reenactments with interviews with key figures such as the late Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah.

360 Darje Muhasireh ("360 Degrees of Siege"), directed by Hamed Hadian, depicts the 89-day resistance of the Iraqi city of Amerli against Daesh (ISIS) and highlights General Soleimani’s role in leading the groundbreaking operation to liberate the city, when many believed its fall was inevitable.

The feature-length documentary Parvaaz Yek o Beest Daghigeh ("Flight One and Twenty Minutes"), directed by Mehdi Naqavian, reveals untold aspects of General Soleimani’s personality through accounts by family, friends, and comrades, focusing on his final days and last family gathering.

Sarbaaz Shast o Seh Saleh ("The Sixty-Three-Year-Old Soldier"), a 16-part series directed by Abbas Vahaj, is the latest documentary, broadcast on the sixth anniversary of his martyrdom, portraying a man who remained a “soldier” from the mornings of Qanat-e Malek to the cold midnight of Baghdad airport.

Together, these works present General Soleimani not as a commander above structure, but as part of a spiritual-organizational order, rejecting excessive individualism.

Their primary function is to create balance in the post-martyrdom space, guarding against hollow myth-making while addressing society’s need to understand a commander who operated for years in secrecy yet held undeniable regional influence.

More than his military genius, what stood out were moments that reminded audiences that his authority stemmed from humility, a clear worldview, and deep love for life and humanity, not from the kind of image-building favored by Western hero narratives.

General Soleimani’s impact on resistance literature was not merely the addition of a new hero, but a transformation of narrative grammar. After him, writing became harder; exaggeration lost credibility; silence became meaningful.

This legacy, before being military or political, is linguistic – and language is the most enduring form of power. Indeed, the essence of this cultural phenomenon in the Persian-speaking world is best captured in the unprecedented title bestowed upon him: “The Commander of Hearts.”

Qassem Soleimani in Arab sources and resistance documentaries

If in Persian literature, General Soleimani evolved from a “war commander” into a “commander of hearts,” in the Arab world, another trajectory unfolded.

Here, he was first and foremost not merely an “Iranian national myth,” but a “comrade in the resistance field” – a real presence in real battles, alongside forces whose states had collapsed or whose armies had been overwhelmed by dangerous terrorism.

This is where the divergence between Arab and Iranian narratives begins: Arab media portray General Soleimani through lived battlefield experience.

Al-Mayadeen Network has been perhaps the most influential in cementing this image. Its documentary Al-Jundi Qassem Soleimani (“The Soldier Qassem Soleimani”) deliberately avoids bombast and emphasizes the word jundi—soldier, not commander.

Built on testimonies from Lebanese, Syrian, and Iraqi fighters who encountered General Soleimani on the front lines, the documentary reviews the 2006 war from his perspective and explores his role in strengthening Palestinian missile capabilities and forming resistance in Syria and Iraq against takfiri terrorist groups.

It also covers Daesh’s advance on Erbil, the breaking of the siege, the formation of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) following the religious edict by Iraq’s top cleric Ayatollah Sistani, and operations against the West-backed terrorist group, ending with images of General Soleimani expressing his longing for martyrdom.

Al-Mayadeen’s Al-Qassem Alladhi Naftaqiduh (“The Qassem We Miss”), directed and produced by Bissan Tarraf, focuses on the emotional dimensions of his relationships and his popular standing across the Axis of Resistance.

With no central narrator, judgment is entrusted to the collective memory of the people whose security he defended as his own homeland. This structure elevates him beyond an “ideal leader” to an “ever-present soldier of sacrifice.”

Another documentary, Zaynab Qassem Soleimani, features his daughter recounting memories from Syria, revealing more interesting facets of her father’s personality.

In Lebanon, Al-Manar Network provides a complementary narrative. On the first anniversary of his martyrdom, Al-Liqa’ Al-Akhir (“The Last Meeting”) depicted General Soleimani’s final encounter with Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, emphasizing his role as a strategic connector among resistance groups while preserving his human traits – patience, restrained humor, and deep respect for local forces.

Other works include Al-Sa‘a Al-Akhira (“The Final Hour”), produced by Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Organization, detailing the events surrounding the Baghdad airport assassination, and the book The Martyr Qassem Soleimani: Icon of Palestinian Resistance, a collection of perspectives on his lifelong dedication to Palestine.

Published in 2023 by the Arab Writers Union and Ard al-Sham Foundation, it features contributions by Syrian, Palestinian, and Iranian scholars.

As Dr. Mohammad al-Hourani, head of the Arab Writers Union, stated at the time: “Although the Zionist enemy succeeded in assassinating the Quds Force commander, Haj Qassem Soleimani, the signs and impact of his resistance remain alive in the conscience of the Palestinian people and the resistance as a whole.”

The “shadow commander” in the enemy’s media

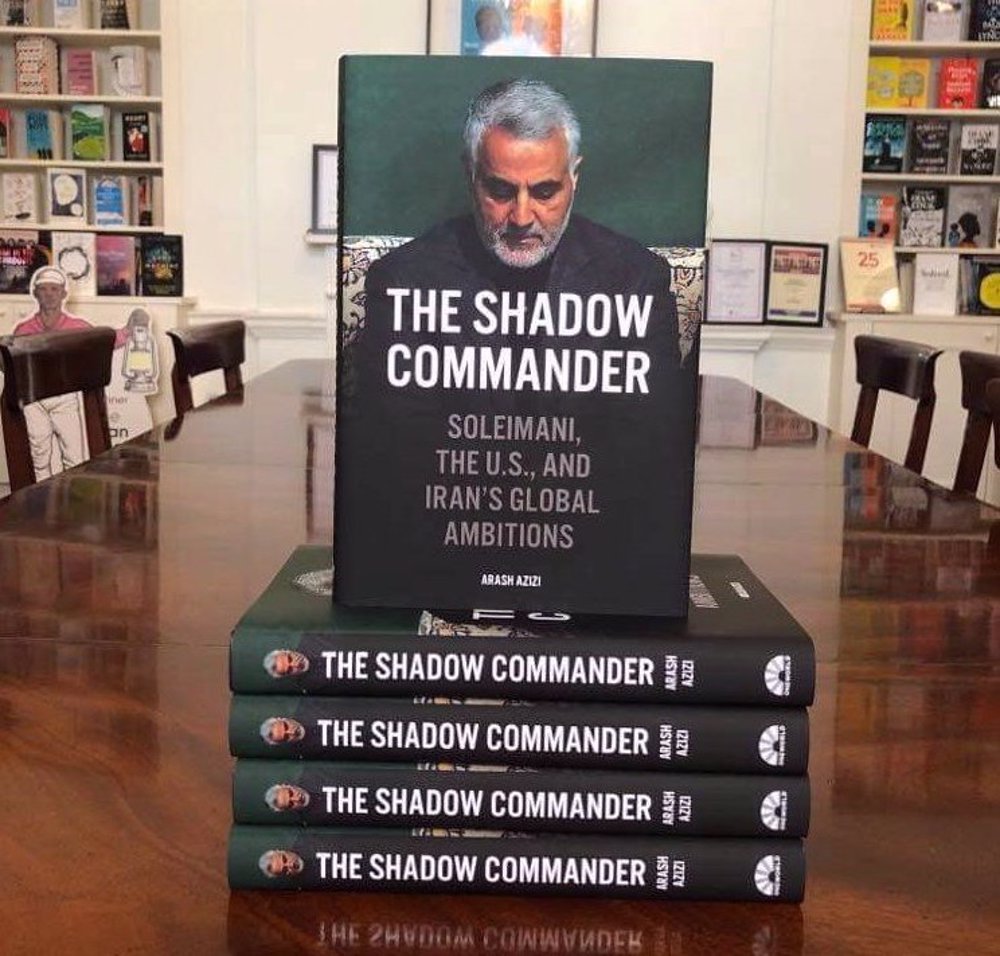

One of the most significant English-language works on Soleimani is The Shadow Commander: Soleimani, the U.S., and Iran’s Global Ambitions by Arash Azizi.

Published in 2020, the book offers a critical, Western-oriented analysis that quickly became a reference in Western and Israeli academic and media circles. Unlike fleeting security reports, it seeks to explain General Soleimani as a history-shaping strategic actor.

British media such as The Times acknowledged that the book demonstrates how General Soleimani turned the battlefield into an instrument of Iranian foreign policy. Analyses by outlets like Paradigm Shift and Middle East Monitor similarly describe him as Iran’s most significant military figure and emphasize his enduring strategic legacy.

Israeli media, including The Times of Israel, explicitly reference Azizi’s work, describing Soleimani as a “larger-than-life figure” who built a resilient regional network.

For Israeli analysts, the book serves not as propaganda but as a tool for “understanding the threat” – not in General Soleimani alone, but in the model he constructed.

Despite Azizi’s critical stance toward the Islamic Republic, his work inadvertently concedes General Soleimani’s unparalleled organizational power, his ability to blend diplomacy with battlefield action, and his central role in shaping new security architecture in West Asia.

Alongside Azizi’s book and the English translation of I Feared Nothing, Western and Israeli documentaries, including those by BBC World, Israel’s Kan 11, and ARTE, acknowledge General Soleimani’s decisive influence.

BBC documentaries described him as the most powerful man in Iraq and recognized his quiet yet formidable authority. Israeli broadcasts went so far as to quote officials calling him “the king of the region.”

The man for all seasons

The convergence of Persian, Arab, Western, and Hebrew narratives leads to a shared conclusion: Qassem Soleimani demonstrated that power does not lie solely in speed or technology.

His charismatic personality, rooted in belief and responsibility toward the Ummah and the oppressed, shaped him into a commander who determined the fate of battlefields.

This is why his legacy is recorded not only in the memories of admirers but also in the language of enemies, who were compelled to write, analyze, and admit. And this, perhaps, is the most enduring form of presence a politico-military actor can achieve in human history.

An Al Jazeera podcast about General Soleimani, which even provoked anger from Al Arabiya, reflected the luminous image of the martyred commander like a sun that cannot remain hidden behind clouds.

In the podcast, Al Jazeera introduced him through a monologue in his own voice:

“I am Qassem Soleimani, a soldier who devoted his life to serving Islam, the Islamic Revolution, and its dignity and honor. I am Soleimani, a mujahid soldier in the path of God, the commander of the Quds Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolution Guards Corps – a name that sends tremors through the Great Satan and the Zionist enemy, feared by the agents of imperialist schemes in our region. Whatever my post may be, I am nothing more than a soldier among the soldiers of the Islamic Revolution. A soldier who praises God, who has purified my heart of worldly attachment and granted me the highest aspiration: martyrdom in His path.”

That and more is General Qassem Soleimani.

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Hamas: Israel escalating ceasefire violations in Gaza

Venezuela's government declares unwavering unity behind Maduro

VIDEO | Global outcry over Venezuela president abduction

Iran keeps wheat import subsidies despite cutting other food supports

Venezuelan military stands with acting president after US kidnapping of Maduro

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Protesters in Toronto slam US kidnapping of Venezuelan president

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website